Geothermal Energy (Part 3)

Written by Amardeep Dhanju

January 30, 2026

In the previous blog posts on geothermal energy (Part 1 on December 4 and Part 2 on December 17, 2025), we described geothermal energy, introduced Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS), and discussed various types of EGS technologies. EGS represents an exciting advancement in geothermal technology, with the potential to become a much larger contributor to needed renewable generation. In this post, we’ll take a closer look at the resource potential, key benefits, technical challenges, and environmental impacts of EGS technologies.

Enhanced Geothermal System Resource Potential in the US

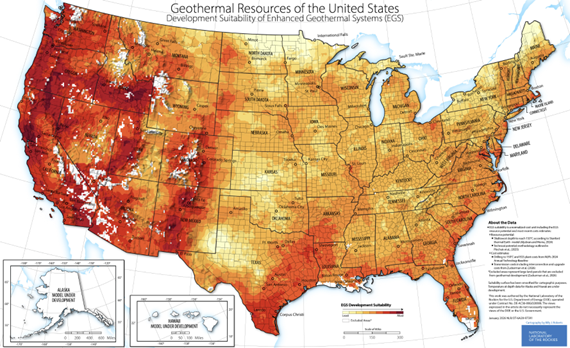

Recent advances and successful field tests have demonstrated the viability of EGS, where heat transport and fluid flow are artificially enhanced through techniques like water injection and rock fracturing. Because high temperatures exist deep below the Earth's surface almost everywhere, EGS can be deployed across broader regions than just those with shallow subsurface heat (as required for traditional geothermal power generation). The map below reflects the development suitability of EGS in the continental US. The most suitable areas are in the western US, where higher temperatures are generally reachable at shallower depths with favorable geology, whereas in other regions they exist much deeper underground, making EGS technically possible but currently less viable.

A 2024 study published in Nature Scientific Reports journal estimates that there may be as much as 83,000 GW of EGS potential across the US. Today, conventional geothermal facilities have a combined installed capacity is roughly 4 GW (or about 0.3% of the United States total power generation capacity of 1,300 GW). Most of the EGS potential lies in the western and southwestern states, with California, Oregon, Nevada, Idaho, Utah and Colorado representing the highest resource availability. Developing even a small fraction of this resource could deliver a significant supply of reliable, clean baseload power.

Development Suitability of Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS). Source: National Laboratory of the Rockies.

Benefits of EGS Development

The 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) preserved the tax credits (Production Tax Credit and Investment Tax Credit) for geothermal power generation, including EGS projects, allowing facilities that begin construction through the end of 2033 to qualify. The potential growth of EGS in the US will benefit from a skilled workforce drawn from the oil and gas sector, providing a strong foundation for rapidly developing this type of geothermal energy. EGS presents a transformative opportunity to expand geothermal energy generation into areas beyond the limits of naturally occurring hydrothermal resources offering advantages such as design flexibility, improved siting options, and synergies with existing energy infrastructure, as described below. Key advantages of EGS (as compared with traditional geothermal) include:

Much broader resource availability than traditional geothermal generation: EGS creates permeability in hot, low-permeability rock, enabling development in areas without natural hydrothermal reservoirs. By drilling deeper and engineering the reservoirs, EGS can access higher temperature formations, improve thermal efficiency and dramatically expand the geographic footprint where geothermal energy can be harnessed.

Enhanced design flexibility: With EGS, geothermal reservoir characteristics (such as size, fracture connectivity, and circulation rates) can be engineered and actively managed by the operating engineering team. This control allows operators to optimize output, minimize thermal drawdown,[1] extend reservoir life, and even modulate injection and production rates to ramp power generation up or down as needed by controlling the flow of injected water and resulting hot water or steam production.

Significant siting flexibility: Because EGS does not rely on naturally occurring rock permeability or shallow geothermal resources, projects can be sited across much larger areas. For the areas shown in the map above with highest generation potential, this siting flexibility may allow development closer to transmission or electricity demand centers, including industrial clusters, manufacturing hubs, and emerging high-power loads such as data centers.

Ability to use alternative working fluids: Certain EGS concepts use carbon dioxide (CO2) in supercritical phase – where CO2 exhibits liquid-like density and gas like viscosity - or using CO2 dissolved in brine as a working fluid instead of water, thereby reducing water consumption, lowering pressure requirements, and offering simultaneous geologic CO2 storage. This approach offers additional benefits, including improved heat extraction, reduced pumping cost due to low viscosity and higher thermal expansion, and minimized scaling and corrosion of equipment (as compared with use of water). Other fluids that have been explored include hydrogen, nitrogen (N2) and nitrogen oxides (N2O).

Workforce and infrastructure synergies: EGS leverages decades of innovation from the oil and gas industry, including directional drilling, high-temperature tools, advanced rock fracturing methods, and a skilled workforce, accelerating deployment and helping to reduce power-generation costs.

EGS reservoirs can also serve as energy storage media: Electricity generated by intermittent generation sources (e.g., solar and wind) can be used to inject water into EGS reservoirs where hot water or steam would accumulate and build up pressure. This resource can be tapped via production wells to generate dispatchable electricity that can quickly ramp up and down within minutes. A 2022 study published in Applied Energy journal discusses this concept.

Risks and Environmental Impacts of EGS Development

EGS development has the potential to create the following environmental and operational impacts or challenges:

Induced seismicity: Fluid injection and rock formation stimulation (fracturing) can modify subsurface stress conditions and trigger minor earthquakes. Contributing factors include proximity to critically stressed faults, high injection pressures, rapid pressure changes, and inadequate subsurface characterization. These potential triggers can be controlled or reduced with careful site selection, detailed geo-mechanical modeling, phased low-rate stimulation, adaptive injection control, and strong regulatory oversight.

Well integrity and groundwater protection: Loss of well integrity could allow injected fluids or formation brines to migrate into freshwater aquifers.[2] Mitigation measures include robust well design, installation of multiple protective barriers while drilling through freshwater zones to minimize risk.

Water demand: Well stimulation and power generation operations may require substantial water volumes, which could affect local groundwater supplies and nearby groundwater users. The use of non-potable water, and recycling produced fluids can reduce freshwater use.

Noise, aesthetics, and habitat impacts: Construction of well pads, roads, generation facilities, and transmission infrastructure can fragment habitats and create noise and aesthetic impacts for nearby property owners or recreationists. Impacts can be mitigated by siting in previously disturbed areas, minimizing pad size, consolidating infrastructure like transmission lines and pipelines in existing utility corridors, and applying seasonal restrictions to protect sensitive and endangered species.

Technical Challenges of Enhanced Geothermal

EGS projects can encounter a range of technical hurdles that could impact cost, operational performance, and public acceptance. These hurdles include:

The need to access higher temperatures requires drilling of very deep wells: EGS wells typically reach depths of 4-7 kilometer (2.4 to 4.3 mile) depths, where rock temperatures can exceed 250-300OC. These extreme conditions accelerate wear on drill bits and downhole tools, increasing drilling time and cost.

High temperature environments can cause degradation of electronics and instrumentation: Prolonged exposure to high temperatures degrades sensors, power systems, and control electronics used for directional drilling, monitoring, and reservoir management, reducing data quality and tool lifespan.

High subsurface pressures increase the instability of each wellbore: Extreme subsurface pressures increase the risk of wellbore instability, including collapse of wellbore walls, lost circulation, and casing deformation. These risks can be mitigated through additional casing, enhanced cementing, and meticulous geotechnical planning.

Drilling for deep subsurface heat leads to uncertainty about the geologic formations likely to be encountered: Variability in permeability, stress, temperature, and fluid chemistry can affect the predictability of reservoir performance, with implications for circulation efficiency, power output, and project economics. Continued advancements in high-temperature materials, downhole sensing, and reservoir modeling can help reduce these uncertainties.

EGS Demonstration Projects

The U.S Department of Energy (DOE) has funded multiple large-scale EGS demonstration projects, generating important data and scientific insights that may advance EGS technology. Following are examples of projects funded by the DOE:

Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy (FORGE), led by the University of Utah, is an ongoing dedicated field site for testing and advancing EGS technologies. This initiative focuses on understanding the key mechanisms behind EGS success, particularly how to create and maintain fracture networks in rock formations. Research and development efforts include innovative drilling methods, reservoir stimulation techniques, well connectivity and flow testing, and related activities. FORGE was launched in 2014 and remains active.

Starting in 2008, DOE funded multiple EGS projects including Newberry Volcano (Alta Rock Energy, Oregon), The Geysers EGS Demonstration project (Calpine Corporation, California), Ormat Desert Peak 2 (Ormat Technologies, Nevada), and Raft River (University of Utah, Idaho), with funding levels ranging from $4.5 million to $21.4 million.

These demonstration initiatives are vital for reducing costs, applying best practices from oil and gas sector, and accelerating the commercialization of EGS.

Conclusion

Unlike intermittent renewables such as solar and wind, EGS can provide baseload power, making it an important complement to variable energy sources. While technical and environmental challenges remain, reservoir engineering and sensing technologies, supported by favorable policies and strategic initiatives, are driving steady progress. With sustained investment and continued development, EGS has the potential to significantly expand the nation’s renewable energy portfolio, strengthen energy security, and support ambitious climate and decarbonization goals.

[1] Thermal drawdown happens when the injected water cools the geothermal reservoir, leading to a decline in produced water temperature and, consequently, power generation output.

[2] Well integrity refers to a well’s design, construction, and protective barriers to safely isolate injected fluids and formation brines from surrounding formations - particularly freshwater aquifers- throughout drilling and operation.