Geothermal Energy (Part 2)

Written by Amardeep Dhanju

December 17, 2025

(Part 2 in a series of blog posts on Geothermal Energy)

Traditional geothermal energy generation (see Part 1 of this blog) has been used since the early 1900’s and is largely limited to regions where subsurface heat lies relatively close to the Earth’s surface. Recent technological advances, however, are unlocking geothermal resources across a far wider geographic area. While conventional geothermal relies on naturally occurring heat, fluids, and permeability, Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) makes it possible to extract heat from rock formations that were previously inaccessible. This blog post explores EGS’s vast potential, and the various techniques used to harness the resource.

What are Enhanced Geothermal Systems?

While traditional geothermal relies on naturally occurring subsurface heat, EGS creates man-made reservoirs within hot, low permeability rock. The process involves drilling wells into thermal formations and injecting water at controlled pressures to induce or enhance fractures, establishing a subsurface circulation network. As water moves through the engineered reservoir, it absorbs heat and is pumped to surface through a production well to generate electricity before being reinjected to sustain the system. In the oil and gas production, a similar technique is called hydraulic fracking, or “fracking.” The major distinction is that EGS uses water without the chemical additives commonly associated with oil and gas fracking.

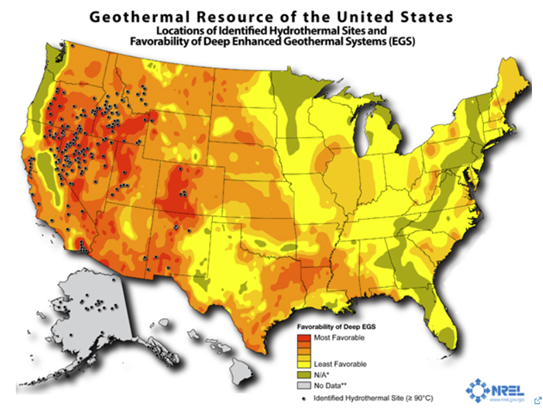

Like conventional geothermal, EGS converts subsurface heat into reliable, renewable baseload power. But unlike conventional systems, EGS can operate in areas where subsurface formations are not naturally permeable or where aquifers do not exist, significantly expanding the geographic potential for geothermal energy. According to analysis by DOE’s National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR), as shown in the map below, the potential footprint of EGS across the United States is extensive.

Source: National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Geothermal Maps.

Notes: “N/A” regions have temperatures less than 150°C at 10 km depth and were not assessed for deep EGS potential. Data on Alaska and Hawaii are not available.

Below is a summary of the primary types of EGS. These approaches vary in how circulation pathways are created and the technologies used to extract heat. Together, they illustrate the diverse ways EGS can unlock previously untapped geothermal resources.

Hot Dry Rock (HDR) Systems

HDR involves creating an engineered geothermal reservoir in dry, hot rock formations, typically granites, that contain high temperatures but little to no natural permeability or fluid. Two different types of wells are drilled, one for water injection and one for production of hot water or steam. Water is injected under pressure to create fractures, circulates through the newly created reservoir, and then is pumped to the surface using a production well to generate electricity. An example is the Fenton Hill EGS project in New Mexico, which demonstrated sustained heat extraction from hydraulically fractured granite reservoirs at depth of roughly 2.6 km. The project was a groundbreaking research effort, however it did not produce commercial electricity.

Hot Wet Rock (HWR) Systems

HWR systems target hot rock formations, whether crystalline or sedimentary, that naturally contain fluids but lack sufficient permeability for commercial geothermal production. Wells are drilled into the reservoir, and hydraulic and thermal stimulation are used to open or enlarge fractures and create viable flow paths. Water circulates through the stimulated reservoir, returns to the surface to generate electricity and is reinjected to sustain the system. Because HWR relies on both natural fluids and engineered permeability, it serves as a bridge between conventional geothermal and classic HDR systems. An example of the HWR system is the Raft River EGS in Idaho.

Closed-loop Advanced Geothermal Systems (AGS)

This technology represents a fundamental departure from traditional geothermal approaches. Rather than relying on natural or engineered permeability, these systems circulate a working fluid through sealed pipes installed in hot subsurface formations. Heat is transferred conductively from surrounding rock into the fluid, which is brought to surface for power generation before recirculating. Because AGS does not produce or reinject formation fluids, it avoids issues like managing corrosive brines, maintaining reservoir pressure, or navigating complex water-handling regulations that affect open-loop systems. An example is the GreenFire Energy Inc. closed-loop demonstration at Coso geothermal field in California, the world’s first field-scale AGS system. The project generates around 1 – 1.2 MWe of net electric power.

Supercritical EGS

Supercritical EGS integrates advanced drilling and stimulation techniques with the exceptionally high energy potential of supercritical fluids – water heated to conditions where it is neither a liquid nor a gas. These conditions typically occur at depths of 1,000 feet or more below the earth’s surface, where temperatures approach 400OC and pressures exceed 200 times atmospheric pressure. Supercritical water flows more easily through fractures and can deliver five to ten times more energy per well than conventional high-temperature geothermal systems, reducing the number of well needed and significantly lowering overall project costs. However, accessing these depths where temperatures and pressures are extreme is technically challenging, as standard drilling tools and electronics can fail under such high temperatures and pressures. Specialized high-temperature equipment is now being designed to overcome these limitations. An example is Mazama Energy’s Newberry Volcano Superhot Rock (SHR) demonstration project in Oregon.

The following DOE graphic illustrates the typical development sequence for EGS.

EGS Reservoir Development and Operation (source: Department of Energy)

Conclusion

EGS hold an immense promise for a clean, reliable, and flexible energy future. By unlocking the Earth’s heat, geothermal energy can provide firm, carbon-free power, support grid stability, and reduce dependence on fossil fuels. Beyond electricity generation, EGS could also enable direct-use applications and industrial heat processes, creating new pathways for significant decarbonization.

In Part 3 of this series on Geothermal Energy, we will discuss the challenges and opportunities in deploying EGS, as well as regulatory developments in California for managing the resource.